I got into sourdough out of curiosity. The more practical-minded need something more than that.

By Chris R. Sims (Simsc) (Own work) [GFDL (http://www.gnu.org/copyleft/fdl.html) or CC-BY-SA-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

What is sourdough?

A sourdough is a dough fermented with a natural leaven. A natural leaven is a rising agent — like commercial yeast, baking powder, or baking soda — that relies on naturally occurring yeasts and lactobacilli. In contrast to baking powder and baking soda, the rising power of natural leavens and commercial yeasts resides in the yeasts. The role of the yeast in fermentation is to convert sugars to carbon dioxide, aerating the dough. I believe these yeasts also generate the complex aromas of naturally risen bread. In contrast to commercial yeasts, natural leaven contains lactobacilli. The lactobacilli convert sugars to acid, providing the characteristic tang.

Why bother?

Four reasons stand out from my experience. The first is flavor, as described above. Nothing compares to a freshly baked country loaf. The depth of flavor and aroma is due almost wholly an effect of the natural leaven. It’s impossible to replicate the effect of natural fermentation. The second is completeness. I still feel like a home cook should know how to bake, or at least try it in order to find out if the costs outweigh the benefits. The third is learning how to be patient. A lot of home cooking is à la minute. Speed is important. But developing layers of flavor often requires time. Rising a sourdough loaf provides a vivid example. It’s changed the way I see food, making me more willing to wait — or rearrange my schedule — to achieve better results. Finally, working with natural leaven provides useful parallels to beer. The plainest rustic loaf contains only flour, water, salt, and leaven. Belgian-style ales contain a similar profile of ingredients. As a reluctant beer drinker who baked sourdough, Belgian-style ales were a relevation. Understanding how those ales were fermented helped me understand other styles of beer, such as India Pale Ales, that tried to achieve similar flavor profiles but by relying more on hops and less on yeasts.

How do I get started?

To bake a sourdough from scratch, one needs a starter. Enthusiasts freely distribute dehydrated starters. One group maintains a sourdough dating from 1847. My brother has used it successfully. I asked for a packet but never revived it. Instead I cultivated a starter myself. It’s a really simple process.

Procedure

- Mix together a batch of “starter food,” consisting of equal parts all-purpose and whole wheat flour.

- Mix together 100 grams of the starter food and 100 grams of water. Store the mixture in a lidded container in a cool place, leaving the lid slighly ajar. This last bit is to ensure gases can escape. Despite many claims to the contrary, this isn’t about capturing wild yeasts floating around in the air. What we’re trying to do is cultivate certain strains of yeast and bacteria that are already present in these flours.

- Check on the starter after a day. If there hasn’t been activity, let the starter sit another day. If the mixture has bubbled up and smells funky, it’s time to feed the starter. Discard 80 percent of the mixture and replace it with equal parts water and starter food. Don’t be scared if the mixture smells bad. When the desired yeasts and bacteria overtake other undesirable strains, the starter will smell pleasantly of beer and overripe fruit. Set the starter back down in a cool place.

- Every subsequent day, repeat the discarding and feeding described above. For now the discards go straight to the garbage. But when the starter is in good shape, it’s easy to put them to good use. Keep observing, i.e. tasting and smelling, the starter. Once it rises predictably and smells as I’ve described, you’ve got your own sourdough starter!

Let me warn you that once you have a starter you may get attached. I cultivated one in Philadelphia and left it behind when we moved. It was a sad day when I realized what had happened. I eventually got over it and cultivated a new starter here in Massachusetts.

Some visual clues

There are many sourdough tutorials on the Web. I felt it worth providing one here because I took videos of my starter’s behavior. Maybe I missed tutorials with this information. Anyway, on to the videos.

Here’s my starter from the beginning through some time on day two. As you can see the initial “bloom” can be slow in arriving. I believe the time-lapse interval was 100 seconds, resulting in a lot of frames being captured:

Note that the sunlight hitting the starter before the starter appears to come alive isn’t actually the cause of the rise. Correlation not causation! If you’re really concerned, check out the right-hand side of the container right before the sunlight hits.

Here’s the starter after the first feeding. It’s day three. Note that I’d initially added way too much water. This explains the floating sludge on top and pool of water on the bottom. I also increased the time-lapse interval to make monitoring my starter remotely less boring:

Day four. Getting closer to equal parts flour and water:

Day five. Note that the rise is less explosive now. Arguably this is evident int he day four video. In my experience and, more importantly, as documented online, this behavior is typical. Don’t lose hope if your starter seems less active as you feed it. Patience:

Day six. Even slower growth:

Day eight. (I didn’t video day seven because I was out of town.) Still slow:

Day nine. Gaining in rising power:

Day ten. More vigorous growth:

At this point I stopped taking videos. I forced myself to taste the starter every day. Both the taste and aroma had started to improve. Based on print and online resources, I knew if I kept up regular feedings I’d have a good, stable starter with which to start baking.

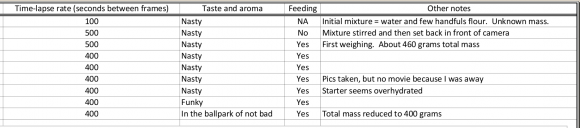

Finally, here are some notes I collected while observing my starter. This is all I have. Hopefully all these materials are useful to someone out there.

I highly recommend Chad Robertson’s Tartine Bread. The book changed my life. It’s one of my all-time favorites, with great instructions exhaustively photographed. If you want to see how baking is done by someone still making rookie mistakes, stay tuned for follow up posts! Learning through someone else’s mistakes is a nice, painless way to learn from mistakes. I know baking isn’t the most practical home activity, so I will pay careful attention to these practical issues of home economics. Another great resource is The Fresh Loaf a site run by and for enthusiasts. It’s great as well.